To Accelerate Change, Microsoft Goes ‘Simple,’ but Not ‘Simplistic’

Microsoft’s culture change journey has been marked by a persistent focus on going simple and establishing its essential leadership principles.

Thank you for searching the NeuroLeadership Institute archives. Here’s what we were able to find for you.

Still having difficulty finding what you’re looking for? Contact us.

Microsoft’s culture change journey has been marked by a persistent focus on going simple and establishing its essential leadership principles.

When leaders create the “conditions for insight,” as NLI calls them, they’re able to unlock the greatest creative potential from their teams.

There are two key habits leaders can build in their cultures to promote speaking up: minimizing a threat state in speakers and those being spoken to.

Continue Reading on strategy+business

Leadership models tend to be exhaustive, rather than essential, which makes them harder to put to use. Research suggests three key habits to focus on.

Reframing a common question around transformation may help leaders reduce the sense of threat often provoked by major change.

When the right people come together, teams can think and act more efficiently. At NLI, we call this balance “optimal inclusion.”

In many organizations, performance management conversations happen maybe four times a year. NLI knows how to make them a regular part of work life.

A key aspect of organizational transformation involves leaders getting buy-in from their teams. But leadership doesn’t come without followership.

The AGES Model helps organizations take a new approach to learning efforts, turning mandatory events into meaningful experiences.

Humans may instinctively resist change, since it threatens our current stability, but research suggests there are ways to reframe change as a positive.

Here’s how leaders create an environment in which both extroverts and introverts feel comfortable sharing their ideas in meetings.

Transformation is on just about every leader’s mind, but not every organization is equipped to handle major change. Science can help.

Every meeting contains some mixture of extroverts and introverts — people who speak up and those who keep quiet. Here’s how to raise quiet voices.

Scientific research suggests there are three key habits around quality conversations that leaders can build to improve employee engagement and retention.

As part of a research project, NLI wants to hear from talent leaders about the leadership models they’ve helped build in their organization.

Emails, texts, chats, and spur-of-the-moment conversations are all common distractions at work. Research suggests it’s hurting organizations’ bottom lines.

Insights, those eureka moments where you suddenly see the world totally different, don’t happen when most people may expect them.

As corporations and governments grow ever more reliant on artificial intelligence to help them make decisions, algorithms have more and more power to influence our lives. We rely on algorithms to help us decide who gets hired, who gets a bank loan or mortgage, and who’s granted parole. And when we think about AI — deep learning and neural networks, circuit boards and code — we like to imagine it as neutral and objective, free from the imperfections of human brains. Computers don’t make mistakes, and the very idea of bias is a uniquely human failing. Right? It’s true that our ancient primate brains, evolved for tribal warfare and adapted for life on the savannah, are riddled with systematic errors of judgment and perception that bias our decisions. As we like to say at the NeuroLeadership Institute: “If you have a brain, you have bias.” But the reality is that algorithms, since they’re designed by humans, are far from neutral and impartial. On the contrary, algorithms have frequently been shown to have disparate impact on groups that are already socially disadvantaged — a phenomenon known as “algorithmic bias.” Just as a lack of dissenting voices in a group discussion can lead to groupthink, as we highlighted in our recent white paper, a lack of diversity in a dataset can lead to algorithmic bias. We can think of this phenomenon as a kind of “digital groupthink.” Consider the below examples of digital groupthink gone wrong: 1. Medical Malpractice Machine learning is a type of artificial intelligence in which a computer infers rules from a data set it’s given. But data sets themselves can be biased, which means the resulting algorithm may duplicate or even amplify whatever human bias already existed. The Google semantic analysis tool word2vec can correctly answer questions like “sister is to woman as brother is to what?” (Answer: man.) But when Google researchers had the system practice using articles from Google News and asked it the question, “Father is to doctor as mother is to what?” the algorithm answered “nurse.” Based on the articles in the news, the algorithm inferred that “father + medical = doctor” and “mother + medical profession = nurse.” The inference was valid based on the dataset it studied, but it exposes a societal bias we should address, not perpetuate. 2. Saving Face In recent years, several companies have developed machine learning technology to identify faces in photographs. Unfortunately, studies show that these systems don’t recognize dark-skinned faces as well as light-skinned ones — a serious problem now that facial recognition is used not just in consumer electronics, but also in law enforcement agencies like the FBI. In a study of commercial facial recognition systems from IBM, Microsoft, and a Chinese company called Face++, MIT researcher Joy Buolamwini found that the systems were better at classifying white faces than darker ones, and more accurate for men’s faces than for women’s. IBM’s system, the Watson Visual Recognition service, got white male faces wrong just 0.3% of the time. Compare that to 34.7% for black women. Buolamwini’s study promptly went viral and IBM, to its credit, responded swiftly, retraining its system with a fresh dataset and improving its recognition rates tenfold in a matter of weeks. 3. Boy Scouts Amazon has long been known as a pioneer of technological efficiency. It has found innovative ways to automate everything from warehouse logistics to merchandise pricing. But last year, when the company attempted to streamline its process for recruiting top talent, it discovered a clear case of algorithmic bias. Amazon had developed a recruiting engine, powered by machine learning, that assigned candidates a rating of one star to five stars. But the algorithm had been trained by observing patterns in resumes submitted to Amazon over a ten-year period. And since the tech industry has been male-dominated, the most qualified and experienced resumes submitted during that period tended to come from men. As a result, the hiring tool began to penalize resumes contained the word “women’s,” as in “captain of the women’s chess club.” To its credit, Amazon quickly detected the gender bias in its algorithm, and the engine was never used to evaluate job candidates. It’s tempting to think that artificial intelligence will remove bias from our future decision-making. But so long as humans have a role to play in designing and programming the way AI “thinks,” there will always be the possibility that bias — and groupthink — will be baked in. To learn more about eradicating groupthink in your organization, download “The Business Case: How Diversity Defeats Groupthink.”

A great deal of research makes it clear that identity diversity matters just as much as cognitive diversity in creating effective teams.

Conventional wisdom says leaders must prepare for specific change events. The reality is change is constant, so adaptability is key.

Groupthink bubbles up when dissenting voices keep quiet. Leaders can improve group decision-making when they work to raise those quiet voices.

Groupthink isn’t invisible. If leaders know how to spot groupthink in their team meetings, they can take concrete steps to make sure it doesn’t crop up.

The Bay of Pigs Invasion, a political move widely viewed as a textbook case of failed decision-making, has helped psychologists study major organizations.

With a continued focus on growth and key leadership principles, HP has managed to dominate its market and see huge gains in engagement.

What causes groupthink? One major factor is the tendency people have in meetings to rush toward consensus, just so the meeting can end earlier.

Exhaustive lists of leadership principles burden the brain, making them hard to remember and nearly impossible to weave into the larger culture.

Groupthink is what happens when team members stop thinking independently, don’t speak up, and race toward consensus. But leaders can still avoid it.

Whether someone speaks up at work or keeps quiet often comes down to their sense of social threat or reward, which leaders play a crucial role in creating.

A focus on growth mindset and building unity through conversations and bias mitigation have helped Nokia create lasting culture change.

Establishing the right priorities are important to create long-lasting change, but leaders also need to implement the right habits and systems.

Our brains crave certainty and loathe uncertainty, both of which make thinking about even the near future extremely difficult.

A shift in mindset — from a fixed mindset to a growth mindset — is the first step leaders need to take in their organization to help kickstart culture change.

Research shows some leaders take growth mindset and run in all sorts of directions with it. To understand why, we can look to the science of learning.

At NLI, we like to say “If you have a brain, you’re biased.” Ever since November 2017, the technology company Splunk has taken that insight to heart.

Changing a culture can feel like just about the toughest job a leader has. It’s hard enough getting yourself to act differently — how could you possibly change the behavior of hundreds or thousands of people? From both our research and extensive client work, helping companies like Microsoft and HP transform their cultures, the NeuroLeadership Institute is confident that all leaders are capable of effecting great change. The key is to follow the science — to know how to shift people’s mindsets to adopt new habits for the long haul. Our latest white paper, “The NLI Guide: How Culture Change Really Happens,” delves into just that topic. The report provides a two-step process that begins with building a growth mindset — that is, the pursuit of always improving, not proving, yourself — and following NLI’s method of Priorities, Habits, and Systems to cement culture change. Every Thursday for the next seven weeks, we’ll be publishing insights from the white paper on this blog, as part of our latest Master Class series. (Catch the last Master Class series, on growth mindset, here.) Table of Contents Week 2: The First Step Toward Culture Change Is a Shift in Mindset Week 3: Leaders Need More Than Buy-In to Create Culture Change Week 4: CASE STUDY: Nokia Turns Two Cultures into One Week 5: How Microsoft Changed Its Culture by Going Simple Week 6: CASE STUDY: HP Embraces Growth Mindset and Kickstarts Culture Change Together, the posts will serve as a handy reference guide for the essential science (and implementation) of culture change. The conventional wisdom around transformation is flawed. It assumes awareness of the challenge or goal is enough. But once you’ve gotten buy-in, then what? NLI’s approach to culture change helps organizations answer that question, so they can make a lasting, scalable impact — and they can do it weeks, not years. [action hash=”1c967ecd-f614-4b3d-a6f1-a14c6ec523bc”]

The research has made it clear: Creating a culture of feedback is the most critical driver of positive organizational and financial outcomes.

Continue Reading on Fast Company

Leaders typically think of growth mindset in terms of performance, personal growth, career development, and skills improvement. But the concept also can be crucial to driving diversity and inclusion efforts. The key: Whether you believe you are capable of improvement often determines whether you think other people are capable of change. That, in turn, shapes how you view your team as a whole. At the NeuroLeadership Institute, we define growth mindset as the dual belief that skills can be improved over time, and that improving those skills is the goal of the work people do. We recently explored this concept in a white paper featuring growth-mindset case studies from five leading global organizations. What science says Research has found a number of benefits to building a growth mindset culture, specifically around inclusion. For instance, growth mindset can reduce stereotyping. Researchers have found that whether or not you think people are fixed or mutable in who they are shapes how many stereotypical judgments people make. If you use a growth mindset, you are more likely to attribute stereotype traits to environmental forces, rather than inborn traits. When making judgments, a growth mindset also helps people gather more information before coming to conclusions. In one study, those with a fixed mindset needed less context before making a decision, potentially leading to undesired or unforeseen outcomes. Growth mindset doesn’t just help people doing the stereotyping; it also helps people on the receiving end. Consider the idea of “stereotype threat.” It’s when members of a certain group do poorly on a task because they’re told they’re not “supposed” to excel. A body of research has shown that growth mindset can reduce the effects of stereotype threat, enabling people to perform closer to their true potential. The business case For organizations, the implication here is that cultivating a growth mindset culture can help drive down biased behavior and create stronger teams. Leaders who help their employees see failures as learning opportunities, and threats as new and exciting challenges, can also help those employees see others’ shortcomings not as signs of personal failings, but merely as a product of being human. When employees start accepting diverse team members as generally well-intentioned, though perhaps fallible, they can move from a culture of competition to one of true and inclusive collaboration. This article is the twelfth and final installment in NLI’s series, Growth Mindset: The Master Class, a 12-week campaign to help leaders see how the world’s largest organizations are putting growth mindset to use. [action hash=”cd97f93c-1daf-4547-8f7c-44b6f2a77b77″]

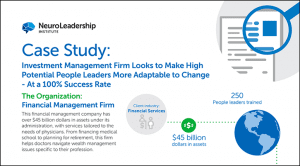

Let’s Start a Conversation Read the Full Case Study KEY INDUSTRY Financial Services PRACTICE AREA Diversity, Equity & Inclusion PRODUCT Trusted as the Diversity, equity and inclusion Partner To Some of the World’s Most Impactful Organizations Case Studies by Practice Area Across industries, we make organizations more human and higher performing through science. These case studies show the change we can co-create. Diversity, Equity & InclusionTake inspiration from firms that mitigate bias and create equitable cultures.Accelerate Inclusion Culture & LeadershipExplore how organizations transform their culture, and shift mindsets at scale.Transform Leadership Talent & PerformanceLearn how companies harness feedback to improve employee retention, engagement and development.Optimize Performance Want to Find the best solution for you today? Commit to Change Connect with NeuroLeadership experts to explore how you can transform your organization at impact, speed, and scale. Scroll To Top

The beloved author H.P. Lovecraft has been famously quoted as saying that “the oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown.” Lovecraft was no neuroscientist or business expert, but in this era of constant change, his sentiment rings true. Organizations face technological advances like never before, creating an ever-growing gap between existing and required skills. At NLI, we believe even the most fearful leader can take solace in the science of perspective-taking, insight, and effective execution, in order to lead a transformation in their organization. Here are three brain-based strategies all leaders can employ. [action hash=”1c967ecd-f614-4b3d-a6f1-a14c6ec523bc”] 1) Use SCARF® to practice perspective-taking Taking others’ perspectives offers many benefits, including seeing new possibilities with clients, colleagues, and even competitors. Perspective-taking facilitates social understanding and increases willingness to engage with others, build relationships, increases perceived leadership capability, and decreases stereotyping. Perspective-taking hinges on three processes: understanding that others possess mental states, realizing those mental states are not identical to our own, and overcoming the self-focused bias of our own perspective. Leaders can use the SCARF® Model — a way of grouping five domains of social threat and reward — to facilitate understanding of others’ motivation and social behavior. Specifically, they should explicitly ask for others’ perspectives, consciously take the perspective of those they seek to understand, and purposefully set aside time to practice. 2) Accelerate breakthroughs by creating the conditions for insight Innovation requires creative thinking, which neuroscience research suggests often derives from moments of insight. Research also shows that there is a reliable series of events that precede emergence of an insight — meaning that it’s not random; it follows a process. Threat and noise reduce the likelihood of insight generation, while a positive mood and relaxed state increase the chance of insight. Leaders can approach team processes with insight in mind by noticing when people tend to have the deepest insights and creating those conditions in daily processes. For example, leaving mornings — when people tend to have the most insights — free for private, quiet work. And allow people to have a few quiet minutes to reflect during a meeting rather than all working aloud. 3) Create extreme clarity for faster execution Uncertainty creates threat, flatlines creativity, impairs decision making, and ultimately diminishes productivity. When people feel threatened, their instinct is to be as careful as possible, often to the point of excess. For instance, role uncertainty breeds indecision and a pathological need for consensus to ensure that everyone is in agreement, which impedes swift progress. To mitigate threat and promote efficiency, leaders should create extreme clarity and set clear expectations in the areas that matter most. These include roles, process, and determining what “good” looks like. Creating extreme clarity in all five SCARFⓇ domains generates a sense of perceived control, which is fundamentally rewarding. Individuals and teams are more motivated to work together and accomplish goals with alacrity through transformation. Indeed, approaching transformation with the right strategies is like folding a paper airplane. Done right, you can make that flat piece of paper soar. [action hash=”1c967ecd-f614-4b3d-a6f1-a14c6ec523bc”]

Across all of our industry research into growth mindset, one question keeps popping up for leaders: If we’re so focused on growth, can we still focus on results? We’ve heard the concern voiced in a number of different ways in discussions with organizations putting growth mindset to use, which we’ve featured in our latest white paper, “Impact Report: Growth Mindset Supports Organizations Through Disruption.” The paper showcases how firms make growth mindset come to life and drive lasting change. In short, the answer is yes. How to measure progress and results We define growth mindset as the belief that skills can be improved with persistent effort; they are not set in stone, or fixed. A Growth Mindset Culture is one where most, if not all, employees demonstrate that attitude in their shared everyday habits. They embrace failure. They take risks. They learn to get better. Fortunately, growth mindset makes room for an emphasis on learning and checking progress over time, because it’s not about comparing two different employees or teams to one another; it’s about comparing one employee or team to themselves. One way to do all that and still ensure you’re moving in the right direction is to perform a bit of mental contrasting. The technique involves holding in your mind’s eye the memories of the past or the vision of the desired future, and contrasting them with the present reality. When leaders contrast where they are to where they were, or where they’d like to go, they can evaluate the fruits of their growth mindset. They can ask themselves questions such as, How much have we grown? Are we growing in the right ways? What else still needs attention? In fact, it’s crucial that leaders encourage their teams to focus on results and learnings, since growth requires two endpoints. A team may never hit certain ideals, but by measuring achievement against specific objectives, leaders can know the growth mindset is working. In other words, growth mindset isn’t important just for its own sake. At some point, everyone still needs to stop and see how far they’ve come. This article is the tenth installment in NLI’s series, Growth Mindset: The Master Class, a 12-week campaign to help leaders see how the world’s largest organizations are putting growth mindset to use. [action hash=”cd97f93c-1daf-4547-8f7c-44b6f2a77b77″]

When collecting data on learning sessions, the net promoter score is the default for many organizations. But there are numerous flaws with the approach.

Leaders are constantly wondering how to create or strengthen their culture. So as part of its ongoing NLI Guide series, the NeuroLeadership Institute has released its latest white paper, “How Culture Change Really Happens.” In simple, everyday language, the guide makes a compelling case that leaders should be pursuing two lower-level objectives in order to produce — and sustain — culture change. Without both elements, teams may start working more efficiently, but the behavior is bound to subside. NLI’s approach to culture change starts with growth mindset. Leaders must help their employees understand that mistakes happen, and that failure is inevitable. What matters is whether people see those setbacks as reasons to give up, or to persist. Once people start embracing challenges as opportunities, rather than as threats, NLI believes the next step is PHS: priorities, habits, and systems. Leaders often make the mistake of thinking awareness of a goal is enough motivation to achieve it. But willpower is fleeting, so it’s important to create the habits that support a change, and the systems that reinforce those habits. We define culture as shared everyday habits. With a growth mindset and a focus on priorities, habits, and systems, leaders should have no trouble building the desired shared everyday habits in their own organization. [action hash=”1c967ecd-f614-4b3d-a6f1-a14c6ec523bc”]

By now, most leaders understand that organizational growth mindset is a transformative tool for talent development. The belief that others can develop their abilities — and the ability to help them do so — are powerful ways to help employees become more resilient, more nimble, and more innovative. But actually putting all that into practice within an organization is more difficult than it sounds. As we recently learned in our industry research project — an endeavor we captured in a new white paper, “Growth Mindset Culture” — leaders are finding that two main obstacles keep getting in the way. Here’s what they’re about and how to address them. Obstacle #1: An imperfect understanding of growth mindset When it comes to cultivating growth mindset within an organization, it’s not enough for leaders to simply tell employees to have a growth mindset. Nor should leaders simply declare that they themselves have a growth mindset when the reality is that many leaders don’t fully understand it. For leaders to really embody growth mindset, they need to ask themselves: Do they truly believe in their own need to grow, and not just that of their employees? The best way to promote growth mindset throughout an organization, we’ve found, is for leaders to embody growth mindset themselves. Our research showed that leadership buy-in was critical for the success of growth-mindset initiatives. To assess their own understanding, leaders should ask themselves three questions: Do I believe that everyone in their organization has the capacity to grow? Do I believe there’s talent everywhere in the organization — talent that should be fostered and acknowledged as it emerges? Am I open about my own mistakes, and the lessons I draw from those mistakes? Only when leaders understand these principles fully, deeply, and accurately can they truly serve as models of growth mindset for their employees. Obstacle #2: Policies that don’t reflect a true commitment to growth Once leaders begin to master the principles of growth mindset, they can turn their attention to disseminating it throughout the organization. But fostering a culture of growth mindset requires more than just sending out a few emails or running a training workshop. It also means revising practices, policies, and systems throughout the organization to make sure they value not just performance, but learning, growth, and progress over time. Unfortunately, many organizations that claim to value growth mindset treat their employees in a way that doesn’t value their growth — for instance, firing an employee who makes a mistake rather than treating it as an opportunity to learn and grow. When this happens, it signals that the organization may be overvaluing performance relative to growth. The key to creating a supportive environment is communication. Employees and managers should speak frequently in a constructive evaluation process. They should discuss what they’re really happy with, what can still be improved, and how to collaborate on getting there. Ultimately, organizations that truly care about employees’ growth and development know that making mistakes is inevitable — and they foster an environment where mistakes are seen not as indictments of worth or ability, but as opportunities for growth and improvement. This article is the ninth installment in NLI’s new series, Growth Mindset: The Master Class, a 12-week campaign to help leaders see how the world’s largest organizations are putting growth mindset to use.

The key to addressing toxic behavior might be the third person in the room. A new study of more than 6,000 college students suggests a major way to reduce toxic behavior is through bystander training — that is, equipping people who witness instances of assault, or possible warning signs, to quickly intervene. People who underwent training intended to act and actually did more much often than those who weren’t trained. The finding bolsters what the NeuroLeadership Institute has found with respect to “employee voice,” or the extent to which employees feel empowered to make constructive, challenging upward communication like calling out harassment or other toxic behaviors. Multiplied across an entire organization, cultures of speaking up may hold the power stamp out toxic behavior, creating a cultural impact that goes beyond compliance training. Bystanders play a crucial role Good-faith arguments that recipients of toxic behavior should speak up themselves make sense in theory, but for many who experience assault, bullying, or harassment firsthand, the pain and confusion is much too paralyzing. In turn, negative feelings get internalized, and toxic behaviors may go unchecked. The new study, led by Clemson University sociologist Heather Hensman Kettrey and published in the Journal of Youth and Adolescence, suggests an alternate path toward safer and healthier work environments. Kettrey found that training programs designed to encourage witnesses of sexual assault or predatory behavior to intervene had a meaningful effect on bystander behavior. Program participants both intended to take more action and did take more action in the months following the training — two times more often, on average — than students who hadn’t gotten trained. “These findings are especially important considering that research indicates that traditional sexual assault programs, which target the behavior of potential victims or of potential perpetrators, are not particularly effective at preventing assault,” Kettrey writes in The Conversation. “Thus, the power to prevent sexual assault may lie in the hands of bystanders.” The importance of focusing on culture When lower-status people feel targeted by higher-status people, fears of retribution or other social threats prevent them from speaking up. Bystanders don’t necessarily fit into the same power dynamic, enabling them to act as neutral advocates on behalf of the lower-status employee. It’s in leaders’ interest, in other words, to create better bystanders and cultivate a culture of speaking up. To do this, leaders need to instill the right day-to-day habits across their organizations. For instance, they can create clear if-then plans to give employees a sense of certainty if an ambiguous situation may arise. Rather than sit idly by, worrying if they’ll get punished for speaking out, a bystander can turn to the if-then plan everyone agreed upon. This kind of intervention is different from the norm because it goes beyond compliance. It gives leaders behavioral tools to enable all employees to speak up early and often. In cultures of speaking up, employees value consequences. Bad actors can’t slip under the radar because warning signs get reported long before they reach a boiling point. “We, as a society, should strive to become better bystanders by noticing the warning signs of a potential assault, knowing strategies to intervene, and remembering that we have a collective responsibility to prevent sexual assault,” Kettrey writes. The same is true in the workplace. Teams composed of better bystanders create a common good in the larger culture, which enables everyone to feel free and safe to get their best work done.

Just because leaders have made growth a near universal priority, doesn’t mean that they necessarily know how to implement growth mindset. New data from the NeuroLeadership Institute makes that gap clearer than ever. Results from a recent survey* showed a whopping 48% of people, when asked about the top obstacle for kickstarting growth mindset in their organizations, said it was the uncertainty of how to put growth mindset into action. Interpreting the data To us, this result indicates that leaders still feel they lack the tools to build a “growth mindset culture,” or one in which employees embrace failure and see challenges as opportunities, not threats. It also suggests that people feel uncertain about the business case for growth mindset in organizations. Alternatively, they may feel unsure how to get others to care about its potential relevance to performance. All these doubts may accompany the ever-present misunderstandings and old myths around what growth mindset is and is not. Equally telling, our survey showed that 25% of respondents felt existing systems discourage growth mindset from taking shape. This highlighted for us the importance of creating work and talent processes in a way that support, not oppose, a growth-mindset approach. For example, if your talent management approach worships innate talent and drives a highly competitive environment, employees may try to nip growth mindset initiatives in the bud fairly quickly. Where to look for growth mindset The good news is that just 16% of respondents said their senior leaders simply didn’t see the value in growth mindset. Any talent practitioner who ever had to convince top leaders of the need for talent development initiatives know that this is rare. Getting full executive buy in can difficult, and maintaining it even more so. We assume that high-profile leaders such as Satya Nadella, Microsoft’s CEO and avid growth mindset supporter, lead the way by valuing the science behind growth mindset as a performance and engagement driver. To help leaders grasp the science and current application of growth mindset and equip them to make shifts in their own organizations, we captured more such findings from our industry research in our recent Idea Report, “Growth Mindset Culture,” as well as in NLI’s 12-week blog series “Growth Mindset: The Master Class.” Check out either to better understand how growth mindset advocates are make it work in their organizations.

One of the key findings from NLI’s research into growth mindset — the belief that skills can be improved, and aren’t set in stone — is that organizations adopt certain principles to match their existing culture and suit their future needs. Still, even when leaders “make their own meanings,” as we say, they may face difficulty in accepting failures as learning opportunities and seeing challenges as chances for growth. Since no one tells you that building a growth mindset can be so uncomfortable, here are four steps to help you stay on course. 1. Get familiar with the feeling of fear Growth mindset is riddled with uncertainty, one of the key social threats found in the SCARF® Model, a way of organizing unique domains of threat and reward. When we feel highly uncertain, our attention narrows and our cognitive function suffers. When developing a growth mindset in a particular area, it’s important to identify moments of fearfulness to recognize which thoughts may be holding us back. Creating this self-awareness lets people determine whether they really are in tough situation or just new to something. 2. Know you will get frustrated, and that’s okay Developing a growth mindset doesn’t mean that all learning will come easy, and that you will feel great all the time. The key to building growth mindset is to recognize that setbacks are inevitable, and also temporary. Learning requires a willingness to figure out how to make progress and move forward despite initial frustrations. Sometimes the best remedy to a challenge is rethinking your approach. Taking a break to let past insights marinate can help re-energize you to tackle the problem again. 3. Monitor your progress in order to make adjustments Embracing your ability to grow, develop, and stretch will take practice, and a focus on measuring progress over time. It helps to look at what you’ve learned and where you have room to get even better. As we’ve written before, getting to a state of regular, specific feedback one of the best ways to develop a growth mindset. That means being willing to confront weak spots, concocting ways to adjust, and testing those solutions as soon as possible. 4. Share what you’ve learned and what it took to get there One of the most powerful ways to embrace the discomfort of developing a growth mindset is to share your journey and learning with others. As the G and E in the AGES model for learning suggest, generation and emotion are key to learning. We learn best when we can turn ideas into concrete writing or discussion, and create new energy around it. Sharing your wins and failures may create greater intrinsic reward, which research has shown is extremely motivating. And who knows, you may gain a Growth Mindset Partner as you share your story. This article is the eighth installment in NLI’s series, Growth Mindset: The Master Class, a 12-week campaign to help leaders see how the world’s largest organizations are putting growth mindset to use. [action hash=”cd97f93c-1daf-4547-8f7c-44b6f2a77b77″]

As Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella has put it, leaders should be striving for an organization full of “learn-it-alls,” not “know-it-alls.”

The NeuroLeadership Institute is set to launch a new journal article, “Debunking Gender Myths: The Science of Gender & Performance.” It’s our deep dive into what the research says about how being a woman or a man shapes the way you lead and succeed. In order to broaden the conversation around this incredibly important issue, we are holding a short discussion on Facebook Live on December 4 at 12pm ET with NLI Chief Science Officer, Dr. Heidi Grant. It’ll be an opportunity to ask questions about men and women at work and discover the latest insights emerging from the research literature. To get the conversation going, please submit a question below and we’ll consider it for our on-air discussion. Create your own user feedback survey

Growth mindset means people believe they can get better through practice, not that anyone can become an expert at anything.

Growth mindset, the research indicates, can help leaders adapt to the automation of labor and other forms of the AI revolution.

If you feel stuck, you may have a fixed mindset about growth mindset itself. Here’s how to shift your thinking if you catch yourself using a fixed mindset.

Jam-packed meetings and overflowing project teams don’t do anyone any favors. They cause delays, create confusion, and generally make organizations less effective. At the NeuroLeadership Institute, we view this as a product of over-inclusion — not in the strategic sense, like for hiring, but for more tactical matters. It’s what happens when well-meaning leaders involve more people than necessary to avoid certain people feeling left out. But what leaders really need, according to the brain science, is to learn the tactical habit of “thoughtful exclusion.” We recently explored the concept of thoughtful exclusion for HBR, in a piece titled “How to Gracefully Exclude Coworkers from Meetings, Emails, and Projects.” It makes three basic prescriptions, which we’ve summarized below. Manage cognitive overload Research has found that 3% to 5% of employees at a given organization drive the bulk of collaboration. In turn, they also tend to be the most prone to burnout. Leaders can begin practicing thoughtful exclusion by identifying these employees, and then strategically limiting their involvement in projects and meetings. The technique affirms to people that their input is valued, but also makes clear that not every project deserves the same level of attention. Consider the social brain Humans seek out potential threats and rewards at nearly all times, even in social situations. This means the act of excluding others is intensely emotional (as those who have been left out know firsthand). Specifically, people may feel a threat to their relatedness, or the sense that they belong in a certain group. With the right language, leaders can actively minimize employees’ threat response. For instance, instead of casually mentioning to someone that they are no longer needed on a project, leaders can provide the surrounding context and reasoning for the decision. They can say things like, “I know you’ve already got a lot on your plate, and I’d like to keep you off this meeting so you can stay focused. What do you think?” This is the “thoughtful” component of thoughtful exclusion. It communicates a leader has an awareness of others, and when employees sense that awareness, they don’t feel as threatened. Set the right expectations Addressing people’s social needs is partly a matter of addressing their cognitive needs. The science has made it clear that there’s a great cost to defying a person’s expectations. When our brains think one thing will happen, but then something else happens, the brain uses much more energy to process that new information. Leaders can use this insight to better communicate about particular projects. They can give people strong rewards of certainty and fairness — two other domains of social reward or threat — by being transparent about their decision-making. Each person who enters the meeting will know why they, and everyone else, is there. And everyone who doesn’t get invited will know why, too. When leaders harness the science to get their teams on the same page, they can avoid the pains of politeness and assemble the right talent for each project. As a result, organizations as a whole can start doing more with less.

It’s easy to get overly conclusive when talking about growth mindset, or the belief that abilities can be improved over time. We may say, “Oh, I totally have a fixed mindset,” or “After all these years, I finally have a growth mindset.” But the truth is, that’s inherently a fixed-mindset way of viewing the concept, since it presumes that the mindset itself is set in stone. In reality, people don’t have a fixed or growth mindset; rather, they use a combination of the two depending on the situation. The NeuroLeadership Institute has caught this subtle difference many times over during various industry research projects, most recently culminating in our white paper “Impact Report: Growth Mindset Supports Organizations Through Disruption.” The paper features five case studies from companies making growth mindset come to life and driving lasting change. This variety made it clear that fixed and growth mindsets weren’t “switches” that people turned on or off. They were more like dimmers, capable of being dialed up or down depending on the context. How to actually think about growth mindset Think about your own life. Let’s say you like to cook and sing; maybe you’re learning a foreign language, too. At work you’ve just been promoted and now you oversee a larger team than you did in your previous role. It’s quite possible —probable, even — that you approach each of these domains with a different mindset about your abilities. Perhaps you relish the chance to try new recipes in the kitchen, and add more French to your vocabulary — classic growth mindset. At the same time, you feel like your singing chops aren’t good enough and leadership skills have hit a ceiling, each possibly indicating a fixed mindset. All those scenarios make it impossible to fairly say you have a fixed or growth mindset, because you’re using both all the time. NLI’s research over the past several months made it clear that leaders should go easy on themselves when developing a growth mindset, since the skill itself is something new to nurture. The key is to recognize when thoughts become self-limiting, and then actively work to move toward growth. If leaders can make this mental shift, past research suggests, they’ll be better at instilling growth mindset in their direct reports. In time, they can even create what NLI calls a Growth Mindset Culture — a confluence of growth mindset across an organization, each employee finding more value in getting better as opposed to being the best. This article is the fourth installment in NLI’s series, Growth Mindset: The Master Class, a 12-week campaign to help leaders see how the world’s largest organizations are putting growth mindset to use. [action hash=”cd97f93c-1daf-4547-8f7c-44b6f2a77b77″]

Author and professional poker player Maria Konnikova explained at this year’s NeuroLeadership Summit how leaders can make smarter decisions.

[fusion_builder_container hundred_percent=”no” equal_height_columns=”no” menu_anchor=”” hide_on_mobile=”small-visibility,medium-visibility,large-visibility” class=”” id=”” background_color=”” background_image=”” background_position=”center center” background_repeat=”no-repeat” fade=”no” background_parallax=”none” parallax_speed=”0.3″ video_mp4=”” video_webm=”” video_ogv=”” video_url=”” video_aspect_ratio=”16:9″ video_loop=”yes” video_mute=”yes” overlay_color=”” video_preview_image=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” padding_top=”” padding_bottom=”” padding_left=”” padding_right=””][fusion_builder_row][fusion_builder_column type=”1_2″ layout=”1_1″ background_position=”left top” background_color=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” border_position=”all” spacing=”yes” background_image=”” background_repeat=”no-repeat” padding_top=”” padding_right=”” padding_bottom=”” padding_left=”” margin_top=”0px” margin_bottom=”0px” class=”” id=”” animation_type=”” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_direction=”left” hide_on_mobile=”small-visibility,medium-visibility,large-visibility” center_content=”no” last=”no” min_height=”” hover_type=”none” link=””][fusion_text columns=”” column_min_width=”” column_spacing=”” rule_style=”default” rule_size=”” rule_color=”” class=”” id=””] [/fusion_text][/fusion_builder_column][fusion_builder_column type=”1_2″ layout=”1_1″ background_position=”left top” background_color=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” border_position=”all” spacing=”yes” background_image=”” background_repeat=”no-repeat” padding_top=”” padding_right=”” padding_bottom=”” padding_left=”” margin_top=”0px” margin_bottom=”0px” class=”” id=”” animation_type=”” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_direction=”left” hide_on_mobile=”small-visibility,medium-visibility,large-visibility” center_content=”no” last=”no” min_height=”” hover_type=”none” link=””][fusion_text columns=”” column_min_width=”” column_spacing=”” rule_style=”default” rule_size=”” rule_color=”” class=”” id=””] You and about 20 of your coworkers are sitting around a crowded conference room table, discussing the details of some project. Some people are fighting for attention, trying to get a word in. Others won’t stop talking. Others have tuned the meeting out, retreating to their laptops or phones. At the end of the meeting, the only real outcome is the decision to schedule a follow-up meeting with a smaller group — a group that can actually make some decisions and execute on them. Continue Reading on Harvard Business Review [/fusion_text][/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]

Management transparency has been shown to boost employee engagement, performance, and creativity. But how does transparency drive employee experience?

Change is the only constant, the old adage goes, which might explain why today’s organizations are so focused on adaptation. After spending several months interviewing 20 global organizations about growth mindset, the NeuroLeadership Institute has identified six business reasons an org might look to put the concept to use, which we’ve summarized below. (Note: Percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding.) [action hash=”7b17478f-7c52-499f-9fd4-7a4d4b69cfa1″] 1. Digital transformation (38% of sample) The most popular reason an org might focus on growth mindset was to stay agile in the face of technological uncertainty. Big data and artificial intelligence are rapidly becoming commonplace, and organizations of all kinds — mid-tier companies and corporations alike — are looking to keep talent ready to change on a dime. 2. Business improvement (19% of sample) Some organizations used growth mindset to introduce leaner methodologies into their work streams, restructure teams, or implement new business strategies. These orgs wanted to be more agile, too, but focused more on improving internal operations than adapting to market forces. 3. Growing up (13% of sample) Growth mindset meant just that to some organizations: growth. Maturity stood out as a major reason for organizations that were smaller and looking to expand quickly and sustainably. Financial pressures, internal turmoil, and other setbacks often accompanied these efforts. 4. Reinvention (13% of sample) Organizations focused more on pivoting in some form used growth mindset to change their culture, rebound from financial troubles, and shift gears after a shakeup in leadership. Among these organizations, especially, growth mindset represented a way to see challenges as opportunities, not threats. 5. Performance management transformation (13% of sample) For some organizations, growth mindset was instrumental in overhauling the way they interviewed and hired candidates, and evaluated employees. Instead of asking employees to prove their worth, orgs can use growth mindset to see the value in improvement over time. 6. Quality enhancement (6% of sample) The university in our sample was the lone organization to use growth mindset for accreditation. It saw the concept as the means to enhance the quality of its program for the benefit of current and future students. Parting shots Why one organization might embrace digital transformation over reinvention is a product of the industry and size of each enterprise. A major takeaway from our research is that organizations mold growth-mindset efforts to fit their needs. What works for one might not always work for all, so look for the process in your org that may need growth mindset the most. This article is the third installment in NLI’s new series, Growth Mindset: The Master Class, a 12-week campaign to help leaders see how the world’s largest organizations are putting growth mindset to use. [action hash=”7b17478f-7c52-499f-9fd4-7a4d4b69cfa1″]

In-depth interviews with organizations about growth mindset revealed a fascinating collection of goals, use cases, obstacles, and outcomes.

When Peter Mende-Siedlecki was visiting a loved one in the hospital recently, he noticed something strange by the person’s bed. It was a set of statements, designed to remind the hospital staff of three things. “Please call me _____.” “What I would like you to know about me is _____.” “What I value/love most is _____.” For Mende-Siedlecki, a psychologist at the University of Delaware who’s spent a career studying empathy and spoke at this year’s NeuroLeadership Summit, this was a fantastic discovery. In just three prompts, the hospital engaged in expert individuation, or the psychological practice of seeing people as unique, distinct beings. We can think of it as the opposite of stereotyping. In the workplace, individuation matters because empathy matters. Every day, teams collaborate based on overlapping strengths and weaknesses, constantly keeping others in mind. We sense people’s needs, they sense ours, and everyone adjusts accordingly. The trouble is, science has repeatedly shown that empathy is a scarce resource; our brains don’t want to spend it willy-nilly. This leads to unfortunate observations like “One death is a tragedy, but a million deaths is a statistic,” and the all-too-human habit of “compassion collapse” in the face of mass tragedy, where the brain apparently has an easier time caring about one than many. Individuation, Mende-Siedlecki’s research has found, works as a kind of shortcut to empathy. If we can remember that the people around us feel pain, stress, joy, and all the other things we too feel, maybe we can escape some of the habits that hold us back. Teams don’t necessarily need to mimic the hospital’s prompts to reap the benefits of individuation. Instead, they can model themselves after the behaviors of society’s master networkers — namely, asking one another about aspects of their personal lives, such as where they’re from, who their family is, and how they stay busy, just to name a few. The practice also helps build what Stanford University psychologist Leor Hackel calls “reciprocity.” Hackel, also a speaker at this year’s NeuroLeadership Summit, has found in his research that “paying it forward” through charitable actions or words, builds compassion in people. Creating empathic teams is valuable for leaders because NLI’s own research has found that collective intelligence — even of the emotional kind — is critical for team function. It’s not enough to have a star player, in other words. The best teams are smarter, more creative, and generally higher-functioning because the whole is greater the sum of its parts. It’s an ironic, humanistic takeaway: The more you help employees see each other as individuals, the stronger your entire team will be.

One of the most well-established psychological concepts, growth mindset, has exploded among leadership. But how do you cultivate growth mindset culture?

Organizations often justify a toxic environment and masculinity contest culture with the mentality of “how we do business here.”

Employees that have their social needs met are more likely to feel engaged in their jobs and less likely to look for greener pastures elsewhere.

The future is coming, and getting ready for it isn’t just a matter of more refined thinking, but broadened experiences. This how the US Army War College helps service people prepare for the future, explained Major General John S. Kem at this year’s NeuroLeadership Summit. “What are the gaps for you to be more ready for uncertainty in five to ten years?” he asked. In a military context, according to Kem, it’s partly a matter of taking a tank commander and teaching them to bring diplomacy and economics into their decision-making. In organizations, it means that if you want to become a CEO but you’ve spent your career in marketing, you’re going to have to move into operations or another role to round out your perspective. In other words, it’s all about curing blind spots. At the NeuroLeadership Institute, we put this in terms of experience bias, or the assumption that if you believe something or an experience happened to you, then that must be the only way it could be. But if you go out and seek new experiences, then you’ll work toward escaping that bias. As Kem explains, however, it’s not just a matter of being able to “project into your next job,” but gathering the experiences that will expand our perspectives — and, in turn, be more prepared for uncertainty. That’s a major lesson for managing your own career or designing a talent strategy. It also, we must say, smells a lot like growth mindset: knowing that you can’t possibly know what you need to know from where you are, take the steps to address your blind spots, especially by embracing other disciplines. For more, watch the NeuroLeadership Summit livestream, broadcasting Thursday and Friday.

Facts are facts — except that they’re not. In a session on idea propagation and influence at this year’s NeuroLeadership Summit, Wil Cunningham, a psychologist at the University of Toronto, explained that getting through to people is about more than simply getting things right. What we really need to focus on, he says, are assumptions about the world that they have about how things work. “We treat the world as facts,” he said, “without understanding the structure of belief system the fact operates in.” If we want to reach someone, the research indicates that there are different conceptual gatekeepers to get by. You can convince someone if they think a fact will better their wellbeing. That’s step one. Next, you have to satisfy what’s technically called “the expressive function,” or how a new fact fits within their sense of self and existing web of knowledge. That’s because Cunningham says a lot of the “facts” that we’re trying to impress upon one another are social facts, a concept identified by the French sociologist Emile Durkheim a century ago. Social facts are true to the extent that everybody in a group agrees that they’re true, like that cash has a monetary value rather than being illustrated scraps of paper. “We sometimes hold beliefs to signify the groups we belong to,” Cunningham said. So if you’re pitching someone on a social fact — like that your product solves a common pain point — and it doesn’t blend with their sense of self and group identity, there’s a good chance they’ll reject it. The whole latticework of facts, preferences, and assumptions they’ve long internalized won’t mesh with the new information or argument. If you pass that self-belief test, then you can actually add new fact to their personal web of knowledge, Cunningham says. The takeaway: Get to know your audience — and what they believe about the world — and describe things in those terms, not necessarily your own. That way, you can actually influence people and add insight to their lives. For more, watch the NeuroLeadership Summit livestream, broadcasting Thursday and Friday.

It’s tempting to blame toxic work cultures on an unknowable set of factors, but often the answer is much simpler. In an article for Fast Company, author Meghan E. Butler, partner at Frame+Function, noted that toxic workplace cultures are consistently the product of poor leadership. Specifically, toxic behavior often stems from leaders missing (or ignoring) key warning signs in how teams function. Perhaps they see aggressive work styles as signs of passion, or label cases of bullying as harmless fun. Meanwhile, employees get hurt and the culture turns toxic. Understanding SCARF As Butler points out, there are five key social domains that demand leaders’ attention: status, certainty, autonomy, relatedness, and fairness. We call it the SCARF Model. It relies on the widespread neuroscience finding that social threats register in the brain in a similar way as physical threats: Cognitive function suffers and people’s quality of work declines. Toxic behavior can affect any SCARF domain, or several in combination. For instance, it’s threatening to a person’s status when their co-worker openly calls out a recent mistake in a team meeting. And it damages people’s sense of fairness and relatedness (or sense of belonging) when a manager plays favorites by assigning projects only to certain people. Leaders who stay aware of these domains can actively take steps to fix them, in turn creating more psychological safety at work. That means bestowing employees not with social threats, but rewards. Here are examples for each SCARF domain: Status — Leaders can celebrate employees’ contributions to the wider team, and they can celebrate team wins to the larger department or organization. Certainty — Before starting a meeting, leaders can lay out the agenda and clarify the goals he or she wishes to achieve by the end. Autonomy — Leaders can raise employees’ sense of control and ownership over their work by delegating projects across the team, rather than hoarding information and keeping people out of the loop. Relatedness — Inclusive leaders help their employees recognize shared goals, such as hitting sales targets or wrapping a big project. (Contrary to popular belief, highlighting differences may only further divide people.) Fairness — Leaders can create a sense of equality by mitigating biases, such as seeking diverse opinions around the office to reduce what psychologists call “experience bias.” The takeaway Ultimately, toxic cultures form when leaders practice the same unhelpful behaviors over and over again. These actions are seldom intentionally destructive, but unless leaders actively try to develop the correct habits — and create psychological safety for everyone — social threats are bound to arise. As Butler notes, “All of these signs can generally be whittled down to one key factor: Fear. And fear corrodes mental health and productivity.”

Adaptation requires flexibility, both in mind and behavior. Batia Wiesenfeld knows this firsthand. As the Andre J.L. Koo Professor of Management at NYU’s Stern School of Business, Wiesenfeld has made a career out of looking at the ways employees can change their thinking to max out their productivity, especially when in a state of flux. We recently chatted with Wiesenfeld, a speaker at this year’s NeuroLeadership Summit, about the cutting-edge blend of business and science. NLI: What early interests did you have that led you to your long-term research on organizational change? Batia Wiesenfeld: What has been an abiding interest for me is how people adapt to the challenges of organizational life, having witnessed people who failed to adapt and whose lives were ruined. A friend’s father committed suicide because of a loss of meaning and identity after he was laid off, so there can be serious consequences when you get challenged at work. Work is so important, especially in America. It’s so important given our modern society and how we think about other people. It’s replacing the role of community. It’s replacing the role that family used to play. Now, work is where we feel like we get support, where we define our identity. We often disclose more to people we work with than our family members. So there are these extraordinary challenges and I’m interested to know how people respond to them. That’s what brought me to look at organizational change. I started out with research about things like self-esteem, self-identity, where there is a lot of emotion. And over time, I’ve started to be more and more interested in cognition. NLI: What is your research showing you now? BW: What I’ve realized is that the brain is still so much more in flux than any part of us. At some point, we’ve grown up, we’re not changing, we look the same, but our brains are still changing. Our brain tries to understand the world and adapt to it using mental representations that can range from being very abstract to very concrete. And even that — just thinking about things abstractly or concretely — is an adaptation. If you’re trying to jump beyond the here and now, or think far into the future, you have to be more abstract because the details of the here and now are like tethers that pull you down. They prevent you from making that jump, so even those mental representations are adaptations. On the other hand, all of the concrete details are incredibly helpful for getting things done. When I think of making a presentation today, instead of “I have to present at the Neuroleadership Summit in October,” I can think very abstractly, “Why do I want to do this?” As the Summit date gets closer my thinking gets very concrete. The ability to move in this agile way between more abstract and more concrete thinking is crucial to being able to adapt to our context. In my current research, I’m looking at things like how leaders and followers in organizations that are going through a change have to collaborate because they come in to the change with very different mental representations. The leaders of the organization think big picture, broad vision, way in the future. The followers — the folks who are having to carry this stuff out — they’re thinking about specifics and they’re often somewhat fearful. There has to be collaboration to get the best of both. So I’m seeing that the way we represent our world is so crucial to this phenomenon of adaptation that I’ve been studying for so long. NLI: Where do you see research in this space going in the near future? BW: One is recognizing this confluence of the body and the mind and being much more informed by physiology — neuroscience reflects physiology. It is giving us new insight and we are starting to understand how we can draw from those insights and allow them to inform what we really care about, which are behaviors, especially social behaviors. How are people interacting with one another when they’ve got to get a job done? So now we’re able to see connections. We can draw a line from social behaviors all the way back to the physiological. I see social science and natural science coming together. Data and the ability to process it is part of what’s changing organizations. We have access to so much more information, so much data, and we’re able to do so much more with it such as using it to build theory. I think we used to start from theory and only use data to test it. People are really interested in understanding the future of work, how work is changing, the work experience, and organizations. All of those are changing largely because of technology, and technology is also changing the way we study those things. Vivian Giang contributed reporting for this article. [action hash=”6cd538cd-54dd-4b69-a152-d85ebcd24518″]

Leaders naturally want their employees to bounce back from failures and strive toward improvement — the hallmarks of a growth mindset. But how to cultivate that reality is seldom easy or obvious. Our research at the NeuroLeadership Institute finds better feedback conversations mark the smartest place to start. We define growth mindset as the dual belief that employees’ skills can be improved and that improving those skills is the point of the work people do. The trouble many companies run into, however, is getting people to seek out improvement. Growth mindset is uncomfortable. It requires people to confront their weaknesses, which may feel like personal shortcomings. Regular feedback conversations, in which people ask for feedback rather than give it unsolicited, may help people see challenges as opportunities, not threats. Real lessons from fake negotiations NLI recently published a study that included 62 people from a major consultancy, who were asked to engage in a mock negotiation. Each negotiation was one on one. Researchers behind the study hooked subjects up to heart rate monitors. During the negotiation and in feedback conversations afterward, the heart rate monitors tracked people’s physiological responses. Findings indicated that feedback-givers were just as stressed out as askers. However, those givers who were asked for feedback showed less heart-rate reactivity than givers made to give feedback unprompted. We draw a lot of conclusions from the study. In terms of growth mindset, the biggest one is that asker-led feedback conversations are a lower-stress way for teams to discuss performance. If leaders can encourage team members to ask for explicit feedback on a regular basis, we contend that employees will gradually begin to view critiques as less threatening. They’ll focus less on failures and more on growth. They’ll welcome challenges, not shy away from them. Start small to go broad Leaders play a crucial role in modeling this behavior. According to NYU psychologist Tessa West, an NLI senior scientist and the study’s lead author, it’s still threatening to start asking for feedback. So leaders can use small-stakes questions to get people thinking in terms of improvement, rather than pure wins or losses. For instance, a manager can ask her team what they thought of her eye contact during the last meeting. Performed over and over again, across departments, asking for feedback could hold the power to send a growth mindset rippling across an entire organization. And it all begins with the decision to ask the right questions. [action hash=”6cd538cd-54dd-4b69-a152-d85ebcd24518″]

Due to the effects of bias, managers may be conducting performance reviews in such a way that sets employees on unwanted career paths for years.

Art Markman is a renaissance man of psychological science: He holds a professorship at the University of Texas-Austin, where he’s also the director of the program in the Human Dimensions of Organizations. He co-hosts the podcast Two Guys On Your Head. He’s authored many books, including Smart Change: Five Tools to Create New and Sustainable Habits in Yourself and Others. And he’s also a panelist on the Networking and Building Alliances session at this year’s NeuroLeadership Summit in October. We recently spoke with Art to learn about how immersing himself in motivation and decision science has shaped his life, and came away with some practice advice on how to get more good stuff done in our own lives. NeuroLeadership Institute: How has being in this field change the way you make decisions in your everyday life? Art Markman: There’s a lot of things I’ve done as a result of knowing more. Some of them have been pretty straight-forward. So for example, in my mid-30s I took up the saxophone because there’s all this data that suggests if you look at people’s regrets, the thing that old people regret more than anything else is not the dumb things they did but the important things they didn’t do. And so, I always recommend to people, periodically project yourself mentally to the end of your life and look back and ask yourself, is there anything I wish I would’ve done? And at some point, I thought, “Gosh I always wanted to learn to play a saxophone and I didn’t.” So about a week after that, I went out and found a teacher and bought a saxophone and learned to play. I think I also am better at seeing different sides of situations that I’m involved in. For example, there are broad tendencies to look at other people’s behaviors and assume that it’s being driven by their characteristics, their traits, and individual goals rather than the situation that they’re in. Whereas with our own life, we pay a lot of attention to, “Oh I was forced to do this in this situation.” So I think I’ve become more tolerant of things other people have done by routinely asking myself, “Well, what’s the situation? Did they do this just because they didn’t have a choice? As a result, should I be trying to focus on how to help, how to make that situation better rather than chastising them for some kind of fundamental limitation that they themselves have?” I spend a lot of time writing about behavior change. And so in my own life, like if I want to lose weight, I’m more effective at that because I understand how motivation works. I run this program. I have a staff of 6 people. I have 35 faculty who I work with and I feel like I can work more effectively with people because I have a better understanding of what factors influence behavior change and so we can set up what we do in ways that get people to do things a little bit different, not a manipulative way, but sharing a vision people can get on board with and also structuring a plan where people not only think this is a vision they can be a part of but also something that they can accomplish. NLI: I read somewhere that you lost 40 pounds — how did you do that, and how did your study on motivation help you achieve your goal? When it comes to weight loss, people think to themselves, “I don’t feel right. I don’t look right.” For me, I didn’t like the way I looked and felt anymore. I think that, for one thing, the formula for weight loss is not a carefully guarded secret. Everyone wants some special diet, but at the end of the day, if you’re going to engage in some kind of weight loss activity, you’ve got to burn more calories than you take in and you have to do that consistently. Then the question is, how do you structure your world to facilitate getting more exercise and eating less? It turns out the eating less is probably more important than the exercise. Because you can work really hard, but if you eat too much, you will overwhelm any amount of calories that you burned. There’s a great quote from Jack LaLanne that I love to use, and it’s “The best exercise is pushing yourself away from the table.” But I think what’s important is to structure that environment. One of the things I did was that I became a vegetarian when I wanted to lose weight in part because I figured, rather than just trying to do less than what I was already doing, I thought, “If I completely change the diet that I’m eating, then I have a chance to institute a new set of behaviors.” NLI: You broke the frame, so you’d have to keep paying attention. AM: That was one piece of it. One piece of it was planning a little bit better. If I cooked too much food, then putting the rest away in advance. Some of it was figuring out what to do when I’m faced with a buffet where you want to throw everything onto your plate. It’s really helpful sometime to find dessert plates that are lying around somewhere. They’re smaller plates so you put less stuff on your plate, and then you eat less. So I think there are a lot of ways of messing around with your environment that can help. When I made the decision to lose weight, I let everybody know. People don’t like to do that, because if they fail, it’s embarrassing. But actually when you let everybody know, then they help you. Maybe they choose not to have an ice cream right in front of you. Or they’re a little more sensitive to how they dole food out in front of you if you’re having lunch with them or something. You

Think back to your last feedback conversation at work — how did it go? Chances are, you and your partner felt uneasy, maybe even threatened. The reason is hardly a mystery. Feedback conversations as they exist today activate a deep-seated threat response in the human brain. Even if it’s just a chat, our brains want us to flee. According to a recent article in the NeuroLeadership Journal, research may be able to fix this broken aspect of professional life. In a study led by NYU psychologist and NLI senior scientist Tessa West, 62 participants at a major consultancy engaged in a mock one-on-one negotiation over the price of a biotechnology plant. Then they gave each other feedback on the other’s performance. Heart rate monitors listened all the while. In follow-up analyses, West and her colleague, fellow NYU psychologist Kate Thorson, discovered that giving feedback and receiving feedback were equally anxiety-producing. This was big news: It signaled managers, too, feel the pain of criticism. Even bigger news, however, was that people who responded to a request for feedback — rather than give feedback unprompted, as per typical conversations — experienced significantly lower heart rate reactivity and reported feeling much less anxious. According to West, asking for feedback is better for long-term improvement because it gives people more control over the conversation and certainty in what will be discussed. If people can start small, she says, the initial pain of inviting criticism will eventually lose its sting. “When you ask for feedback, you’re licensing people to be critical of you,” West recently told NLI for Strategy+Business. “It may feel a little more uncomfortable, but you’re going to get honest, more constructive feedback.” Leaders can use the new study as a tool to create more of a growth mindset at work. If everyone begins seeking out ways to improve, instead of shying away from them, entire organizations can adapt more quickly and edge out the competition.