A good deal of our work at Neuroleadership Institute is about finding easily-conveyable, sticky approaches rooted in brain science to help explain core aspects of work, such as motivation, feedback, and more. We want organizations and individuals who attend our training(s) to come away with something easy to recall. Ideally, this easy recall — plus a delivery method that spaces out learning — will help the learning truly resonate with people, and that’s the baseline of habit activation. In turn, habit activation shifts long-term behavior in organizations. It’s a process, but one that works.

It can take literal years for teams at NLI to develop these “sticker” acronyms, and four of the major ones we return to are detailed below for context.

SCARF

This, in some ways, is the “granddaddy of them all” (for college football fans who remember Keith Jackson) of NLI acronyms.

SCARF stands for:

- Status

- Certainty

- Autonomy

- Relatedness

- Fairness

When it comes to workplace interactions, psychology research makes it clear that leaders can maximize engagement and drive lasting performance when they help their team members meet one another’s needs.

So which needs should leaders focus on?

Over a decade ago, a research team led by NLI Director and CEO Dr. David Rock identified five such domains in humans’ social experience.

Briefly:

Status: Status is the drive we feel to stand out from the crowd. When we share our new ideas and take credit for jobs well done, status is that glow of importance we’re looking for.

Certainty: Humans naturally like to know what’s going on. We like to understand our surroundings. At work, we feel threats to our certainty when our roles or responsibilities aren’t totally clear, and when meetings start to go long, without any clear end in sight.

Autonomy: When leaders involve themselves with every little detail of their team members’ work, they risk creating threats to those people’s autonomy. (This is why micromanaging feels so offensive.) However, when leaders give employees the time and space to do their work, unfettered by interruptions, they send a much more rewarding signal that they trust and value the person’s ability to get things done.

Relatedness: Relatedness is the sense that we belong — that we’re in the in-group. Leaders can use language such as “we” and “us” to promote that feeling, instead of language like “you,” “me,” and “they,” which signals a clear boundary between groups. Indeed, political research finds that the collective pronouns predict the chance of a politician getting elected.

Fairness: Lastly, humans innately feel a sense of equity and equality in social interactions. We prefer what’s justified over what’s tilted in one party’s favor.

Leaders can go a long way in promoting fairness through acts of transparency. For example, when making decisions, leaders can communicate their thought process behind making one choice over another. When employees don’t get the full picture, and start to invent alternate stories, it may increase the chance people feel slighted.

You can begin to see how some of the SCARF elements come into play around COVID and its adjacent narratives, including return to work and “The Great Resignation.” In reality, though, a lot of our assumptions about the future of work — hybrid, remote, et al — are just that: assumptions. If you look into the science around the SCARF elements, you can beat back most of the assumptive claims and debates about the future of work.

The SEEDS Model

At the NeuroLeadership Institute, we help leaders and teams mitigate the biases that negatively affect people and business decisions, so that they can be more innovative and effective. Through our research, we’ve organized more than 150 such biases into five broad categories. These five biases comprise the SEEDS Model®, the framework that underpins our solutions geared toward reducing unconscious bias.

The SEEDS Model incorporates:

- Similarity Bias

- Expedience Bias

- Experience Bias

- Distance Bias

- Safety Bias

All five are detailed in this post, as well as throughout our training and consulting work.

Briefly:

Similarity Bias: We prefer what is like us (similar to us) over what is different. It occurs because humans are highly motivated to see themselves and those who are similar in a favorable light. We instinctively create “ingroups” and “outgroups” — boundaries between who we consider close to us and who lives on the margins. We generally have a favorable view of our ingroup but a skeptical (or negative) view of the outgroup. Hence why managers hire employees who remind them of themselves.

Expedience Bias: We’d prefer to act quickly as opposed to taking time (look at some of the decisions about bringing back employees from the pandemic). Humans have a built-in need for certainty—to know what is going on. A downside of that need is the tendency to rush to judgment without fully considering all the facts.

Experience Bias: Our perception becomes supposedly objective truth. We may be the stars of our own show, but other people see the world slightly differently than we do. Experience bias occurs when we fail to remember that fact. We assume our view of a given problem or situation constitutes the whole truth.

To escape the bias, we need to build in systems for others to check our thinking, share their perspectives, and helps us reframe the situation at hand.

Distance Bias: If it’s closer, it must be better than something further away.

Distance biases have become all too common in today’s globalized world. They emerge in meetings when folks in the room fail to gather input from their remote colleagues, who may be dialing in on a conference line.

Safety Bias: We protect against loss more than we seek out gain. Many studies have shown that we would prefer not to lose money even more than we’d prefer to gain money. In other words, bad is stronger than good. Safety biases slow down decision-making and hold back healthy forms of risk-taking. One way we can mitigate the bias is by getting some distance between us and the decision—such as by imagining a past self already having made the choice successfully—to weaken the perception of loss.

The AGES Model

Over the past decade, a great deal of research has identified several key ingredients of successful learning, and the NeuroLeadership Institute has taken notice. Not only do we want to offer brain-friendly solutions to clients, but we want to deliver those solutions in such a way that it creates lasting impact.

What we came up with is a cohesive structure for learning, which we call the AGES Model. It stands for Attention, Generation, Emotion, and Spacing. Together, the AGES Model enables people to learn quickly, and retain that information for the long haul.

Briefly:

Attention: Learning takes place when we activate a brain region known as the hippocampus. This occurs when we focus on one topic, without distractions. When we multi-task or let our minds wander, we’re likely to deactivate the hippocampus and reduce how much learning takes place.

Generation: The second component involves how we engage with the material. Research shows we can’t just absorb information passively; we must take an active, creative role. This stems from how the brain stores memory, as the hippocampus acts more like a web than a hard drive. The thicker and denser the web of memories, the stronger each individual memory becomes.

Emotion: Emotions play a dual role in learning. First, they’ve been found to increase our attention to a given topic, which helps us focus. And second, emotions activate a brain region called the amygdala, which seems to alert the hippocampus that the material is important and worth encoding as memory.

Spacing: Finally, learning takes time. Instead of cramming information into our heads, only to forget it soon after, neuroscientists have long found that the brain really creates long-term memories through a spacing approach. That is, introduce concepts at a steady rate and wait some time before retrieving that information.

The AGES Model is more about how people learn effectively, which is crucial because employees increasingly want to be trained on new skills and with “The Great Resignation” and other narratives of COVID, employers are concerned about getting the best people possible — and that often involves new training, and re-skilling, but those processes must be done in a way where the information sticks. That’s AGES.

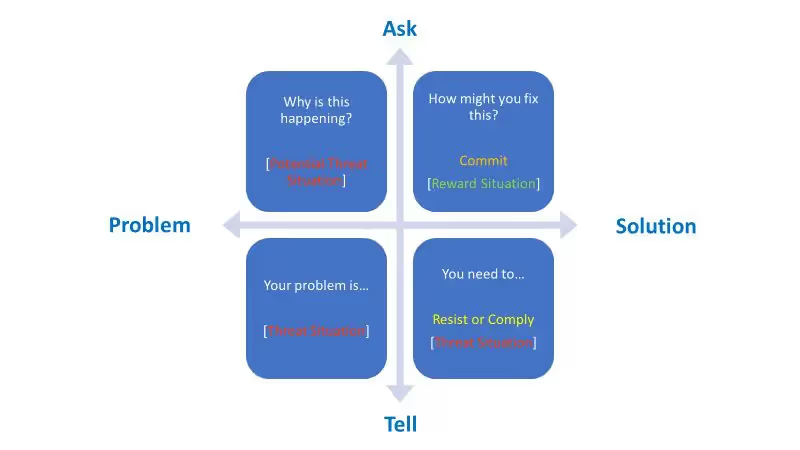

The TAPS Model

We discuss this one less in public-facing work; it’s used more in client work. It stands for Tell-Ask-Problem-Solution, and visually it looks like this:

In sum, this is a way to drive quality conversations and generate more insights from employees, both of which will be crucial to this emergent “FLEX” period of hybrid work becoming normative.

All-in? Ask about solutions, not problems.

Working through the “why” and “how” of issues instead of the more basic questions moves employees towards insight faster — and when you have limited time with them, across distance, this should be your goal.

Other ways that managers can support employees in generating insights, as we mentioned in an October 2016 Harvard Business Review article:

- Let them take breaks between meetings and find some alone time. Encourage an empty conference room or, even better, leave the office and take a walk outside. (Walking might in fact spur your next insight, according to scientists.)

- Allow some downtime on a regular basis — even small doses can have a big impact. Encourage them (and do it yourself!) to turn your devices off for several hours a day – or several days a week if you can. This way your mind will be truly free to wonder, and your brain won’t miss the next light bulb moment when it happens.

- Remember to take a break from any decision-making process. And once you are taking it, focus on something else. Exercise is a foolproof way to take your mind off work, so put a daily workout on your calendar the same way you would schedule a meeting with a client or boss.

All these help employees (and you) find quiet signals — also called “weak activations” — in the brain, which create more A-HA moments and insights.

And overall, asking questions about solutions, i.e. having a real two-way synchronous conversation on the business and the strategy and the long-term, increases reflection and raises a sense of status and autonomy in our brains. Telling? That decreases both. It’s about real conversations and moving employees to insight, as opposed to task-based check-ins.

Questions?

If you have any questions about these models and how they can benefit your organization’s growth through COVID and beyond, reach out and let’s talk more.

.avif)