Jasmine is excited to begin her first job after college graduation: working in a lab at a large chemical company. During employee orientation, safety training emphasizes the importance of eye protection when handling caustic chemicals. So she’s surprised when she begins work in the lab and notices Sam, a decades-long employee, pouring one solution into another without wearing his safety glasses. She wonders if she should say something, but she doesn’t want to start off on the wrong foot with her co-workers — what if Sam tells her to mind her own business in front of everyone?

Many of us have been in Jasmine’s shoes: We see something risky in the workplace but choose not to speak up. In fact, research has shown that when workers see something unsafe, they intervene only about 39% of the time. Usually, it’s not from a lack of caring but from a fear of repercussions. We don’t want our co-workers to resent us. We’re afraid of angry outbursts or being held accountable for bringing a mistake to light. What if we’re wrong, and we waste everybody’s time and look foolish?

But sometimes the consequences of not speaking up can be devastating. Countless disasters, such as the Challenger explosion, the Chernobyl nuclear accident, and the runway crash of KLM Flight 4805, could have been prevented if employees had spoken up and management had listened. In 2021, 2.2 million nonfatal work injuries and 5,190 fatal work injuries were reported in the U.S., both increased from 2020. Few of us face life-or-death situations in the workplace, but even minor injuries cause employee distress and loss of morale, as well as wasted time and money.

The key to reducing workplace injuries is building a proactive safety culture that anticipates and works to prevent accidents before they happen. Employees look out for their own safety and that of others and are not afraid to speak up when they notice a potential problem. Management listens to and acts upon employee concerns without placing blame or punishing, even if it turns out to be a false alarm.

Building a proactive safety culture isn’t always easy. But the stakes couldn’t be higher, and we can use neuroscience to help create the most impactful habits that everyone in a company can implement.

Make safety a value, not a priority

Many organizations claim safety is their top priority. However, when deadlines loom, other priorities can bump it from the top tier. For example, when factory workers are scrambling to meet an end-of-month production goal, they might skip routine safety meetings to save time.

“Think of safety as a value, not a priority,” advises Morgan LeBlanc, CEO of LeBlanc EH&S Consulting Services. “Values don’t change like priorities.” He suggests setting aside 5–10 minutes before each work session to discuss obstacles and hazards that everyone should be aware of. “It’s a time when everyone can speak up. If they don’t have a clear understanding of the job happening that day, they can ask teammates or supervisors,” LeBlanc says.

Cultivate an environment of psychological safety

You’ve probably heard a lot about psychological safety lately, and it’s a critical component of a proactive safety culture. Amy Edmondson, a renowned expert on psychological safety, defines it as “a belief that one will not be punished or humiliated for speaking up with ideas, questions, concerns, or mistakes.”

What’s more, managers should go beyond not punishing to actually rewarding employees for speaking up with safety concerns, notes Michaela Simpson, vice president of research at NLI. “Leaders should acknowledge speaking-up moments in real time and label speaking up as courageous, not troublesome,” she says. They can also role model psychologically safe behaviors, such as asking for feedback in a non-defensive manner, welcoming challenges, and admitting mistakes.

Share the numbers

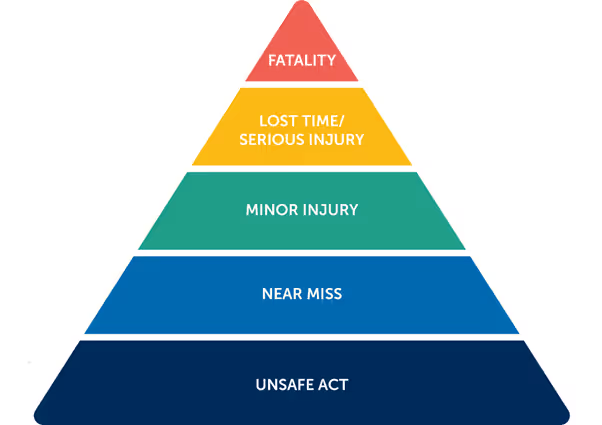

The accident triangle, also known as Heinrich’s or Bird’s triangle, was proposed in 1931 as a theory of industrial accident prevention. It shows the relationship between deaths, serious accidents, minor accidents, near misses, and unsafe acts, suggesting that reducing the number of unsafe acts can cause a corresponding drop in serious accidents and deaths.

LeBlanc suggests that leaders create awareness of this relationship in the work environment. They can implement a simple reporting system, such as a green light that indicates no incidents, a yellow light that signals a near miss, and a red light that reports an injury. Organizations should be transparent in sharing monthly statistics to let employees know how they’re performing on safety. “In quality and production, we’re always looking at numbers,” says LeBlanc. “We should be looking at numbers on safety, as well.”

Create habits and systems that support safety

Even if an organization establishes safety as a core value, if employees aren’t taught the right habits and the organization doesn’t put in place systems to support those habits, they’ll probably fail in reducing accidents. That’s why organizations need to define shared everyday habits that eventually become a social norm. The organization must also establish systems that support the behavior changes they’re trying to achieve.

For example, in 2019, two Boeing airplanes were involved in massive accidents. As a result, company leaders started asking questions: Do people feel safe to speak up? If not, where does the fear come from? With help from NLI, in 2021, Boeing launched their Seek, Speak, & Listen initiative, which reached 96% of their 140,000-employee global workforce. The program trained employees in the “sticky” habits of seek (notice the moment), speak (navigate emotions), and listen (respond constructively).

After reflecting on how she’d feel if Sam ended up getting hurt, Jasmine labels the emotions (fear and embarrassment) that are preventing her from speaking up. The logical part of her brain then recognizes she shouldn’t let these emotions keep her from doing the right thing. So Jasmine waits until she and Sam are alone to approach him. “Sam, do you have a minute? I noticed you weren’t wearing your safety glasses when handling those caustic chemicals, and I’d hate to see you get hurt.”

A flicker of annoyance passes briefly over Sam’s face, then his gaze softens, and he reaches for the glasses in his lab coat pocket. “You know, you’re right. I guess I’ve just gotten out of the habit of wearing these lately. Thanks for caring enough to say something.”

.avif)