In every organization, individual members have the potential to speak up about important issues. But a growing body of evidence suggests that people often remain silent instead, due to fear of negative consequences. At best, this can lead to a lack of diverse ideas—at worst, disaster.

No organization has proven immune to this, as it still happens in rooms filled with the smartest people on the planet. Take NASA, where the issue of speaking up has come into focus several times over the past few decades following notable spaceflight disasters, including the Challenger mission. Now we’re in a new era of spaceflight, and in a move away from government-funded projects, private companies are blasting off and landing rockets, skirting the atmosphere in next-gen spaceships, and targeting missions to Mars.

But will these privately funded endeavors avoid the mistakes of the past? Whoever participates in the next space wave and beyond, there is a lot we can learn from the failed speaking-up moments surrounding these ill-fated flights.

Speaking up lessons from the Challenger disaster

The day before the Challenger launch in early 1986, engineers from the now defunct Thiokol, the company responsible for the rocket booster’s performance, warned that the flight might be risky due to the below-freezing temperature forecast for the morning of the launch.

The O-ring seals, which were classified as a critical component on the rocket motor and a failure point—without back-up—that could cause a loss of life or vehicle if the component failed, had never been tested below 53 degrees Fahrenheit. In the case of the Challenger, the O-ring got so cold it hadn’t expanded properly and allowed the leak.

Yet, during a teleconference 12 hours before launch, when Thiokol engineers raised their safety issue, NASA personnel discounted their concerns and urged them to reconsider their recommendation. But after an internal, off-line caucus with company executives, Thiokol engineers reversed their “no-go” position and announced that their solid rocket motor was ready to fly. And when the Kennedy, Johnson, and Marshall Space Center directors later certified that the Challenger was flight-ready, they never mentioned any concern about the O-rings.

So, why did Thiokol engineers change their minds? They felt pressure from two directions to reverse their “no-go” recommendation. NASA managers had already postponed the launch three times and were fearful the American public would regard the agency as inept. Not to mention, the company’s management was fearful of losing future NASA contracts.

Creating a speaking-up culture with VOICE

The Challenger disaster can be explained as a failure of speaking up—specifically, the failure to question other people’s decisions. Though we may assume that if people have something to say, they’ll say it, the truth is we often silence ourselves due to some form of social threat—that feeling of uneasiness in tense situations.

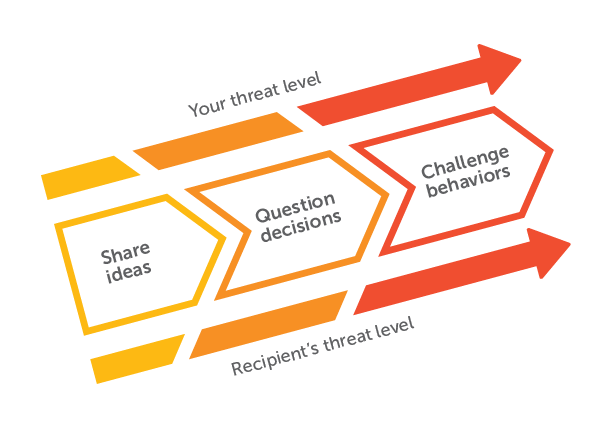

Here at the NLI, we organize acts of speaking up on a continuum—known, fittingly, as the Speaking Up Continuum.

The first situation—the least threatening—involves speaking up to share your own idea. Due to fears that you’ll be evaluated negatively, you may keep the idea to yourself. In the middle of the speaking up continuum lies questioning another person’s decision. Worrying that you are causing the recipient to become upset or defensive, you become more reluctant to speak up. And the most threatening scenario, at the end of the continuum, is speaking up to challenge another person’s behavior, as behavior tends to most often reflect who we are as a person.

The Thiokol engineers’ failure to speak up fell in the second stage: not questioning the decision to go forward with the Challenger mission, due to fears of the repercussions of postponing. Had they managed their sense of social threat, they might have felt more comfortable to do what was right, rather than what was easy.

Organizations can make these types of speaking-up moments easier by helping people spot moments to speak up across the continuum, and creating habits that make challenging conversations more likely to occur. (It’s for just this reason NLI developed VOICE: The Neuroscience of Speaking Up, a solution meant to help leaders create cultures of speaking up.)

Going forward, today’s fleet of space-bound companies can avert disaster by helping employees start speaking up about the small things. Because if people can’t speak up about the small stuff, they may never speak up about the big stuff. And that’s when disaster strikes.

.avif)

.avif)