Here at NLI, we’re in the business of behavior change.

Let’s say your goal as a leader is to change the behavior of the people in your organization. The first step to do this is to let people know what it is you’d like them to do differently — say, by giving them a set of principles to abide by when they do their work and make decisions.

But simply giving people a set of principles isn’t enough. In order for people to actually change the way they do things, they have to be able to remember and access those principles when it actually matters: in the moment, when they’re interacting with colleagues and making real-time decisions — potentially in a high-pressure situation. We call this easy recall under pressure.

Think of what it’s like to master a new language. When you first learn a new word, you might find that it doesn’t always come to mind when you need it. When you look it up again, it’s familiar. That’s recognition, which unfortunately is the level reached by most learning programs today.

A higher standard is recalling with effort — the new word can be called to mind with some difficulty. Better still is recalling easily, such as when you’re talking and the words just flow naturally. But true mastery requires easy recall under pressure. That’s when new words are easily accessible even in a stressful emergency situation.

The same goes for behavior change in organizations. To actually change behavior when it counts, new habits must be easily recallable under pressure.

Three criteria for new habits

To achieve easy recall under pressure, new habits should meet three criteria: they must be sticky, meaningful, and coherent.

First, new habits need to be simple and memorable: brief, easy to remember, and easy to repeat in your head or out loud to a colleague. We call this quality stickiness.

Second, habits must have meaning. To encourage new behaviors, leaders should connect them to something employees care about to provide motivation that serves a greater purpose beyond their career, promotions, or salary.

The third and perhaps most elusive requirement of a new habit is coherence. For new behaviors to be useful in the moment, they need to make sense. Like the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, new information must fit with a person’s existing knowledge and form a consistent, unified whole. That’s because the brain stores memories through networks of connections, and behavior change is most effective when new ideas are mutually reinforcing — closely connected to each other and existing knowledge.

A lack of coherence can cause cognitive dissonance, or the mental discomfort that occurs when ideas and behaviors don’t mesh well, which leads employees to feel conflicted about which actions to take.

Coherence in action

Consider the following paragraph:

If the balloons popped, the sound wouldn’t be able to carry since everything would be too far away from the correct floor. A closed window would also prevent the sound from carrying, since most buildings tend to be well insulated. Since the whole operation depends on a steady flow of electricity, a break in the middle of the wire would also cause problems. It is clear that the best situation would involve less distance.

This set of facts, presented in this way, is extremely difficult to understand or remember. Studies show that our working memory can retain about seven items at once (that’s why phone numbers were originally seven digits long), and the above paragraph is beyond that limited capacity of our brains and working memory. At best, people may remember only a sentence or two.

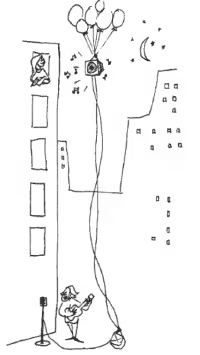

Now take a look at this image:

The image provides a schema — a pattern that helps organize categories of information and the relationships between them. Looking at the image, you understand what’s going on: Some poor romantic soul has jerry-rigged some helium balloons to serenade the object of his affection.

Providing this schema helps you contextualize the paragraph above in a coherent manner. Words and phrases that were baffling at first now fit together. If asked to explain this scene to a colleague, you could.

That’s what it means to be coherent. To learn more about the science behind coherence analysis, tune into NLI’s Summit February 15-16.

.avif)